The science of jump shooting

What Caitlin Clark and Tyrese Haliburton have in common

Caitlin, Tyrese, and NOAH

Here is a clip of Caitlin Clark shooting. Her form was recently described by The Athletic as “optimal,” if not actually perfect.

Credit to The Athletic on the enjoyable compilation there.

Now, here is a clip of Tyrese Haliburton, the All-Star point guard for the Indiana Pacers. His form was recently (and generously) described by The Wall Street Journal as “unorthodox,” if not “the ugliest shot in basketball.”

It’s not pretty.

But Haliburton, before a recent shooting slump, was on pace to make 40 percent of his 3-point attempts for a fourth consecutive season, the fourth-longest streak to begin a career in NBA history. He competed in the 3-Point Contest at All-Star Weekend again this year after reaching the finals in the contest a year ago.

He can shoot, okay. It just might not look like it.

Aesthetically, Clark’s and Haliburton’s form appears quite different. And I’m here to tell you: That’s okay.

Physics of jump shooting

In 2008, two mechanical and aerospace engineers at North Carolina State University, Larry Silverberg and Chau Tran, analyzed hundreds of thousands of shot trajectories from NBA shooters using a computer simulation. They were looking specifically at free-throw shots, which are the simplest to objectify, but they landed on what they considered to be a few keys for “optimal release conditions” that could apply to any jumper.

Shooters should launch the shot with about 3 hertz of back spin, or with the goal that the ball makes three complete backspin revolutions before reaching the hoop.

Aiming for the center of the basket decreases the probability of a successful shot by almost 3 percent. Aim, therefore, for the back of the rim.

The proper “launch angle” on the shot should be 52 degrees. Roughly speaking, it means that the shot at its highest point is less than 2 inches below the top of the backboard.

Release the ball “as high above the ground as possible” along a straight imaginary line between the player and the basket

Maintain as smooth a body motion as possible to get a consistent release speed.

“A little bit of physics and and a lot of practice can make every a better shooter,” the authors wrote, adding: “You know who you are, Shaquille O’Neal and Ben Wallace.”

Now, I have no idea if Caitlin Clark’s typical launch angle on a jump shot is precisely 52 degrees! But the University of Iowa probably does. It also utilizes what’s called the NOAH Basketball system, which tracks how shots enter the rim from a camera positioned above the hoop — similar, in a sense, to what the TracMan does for golf or baseball.

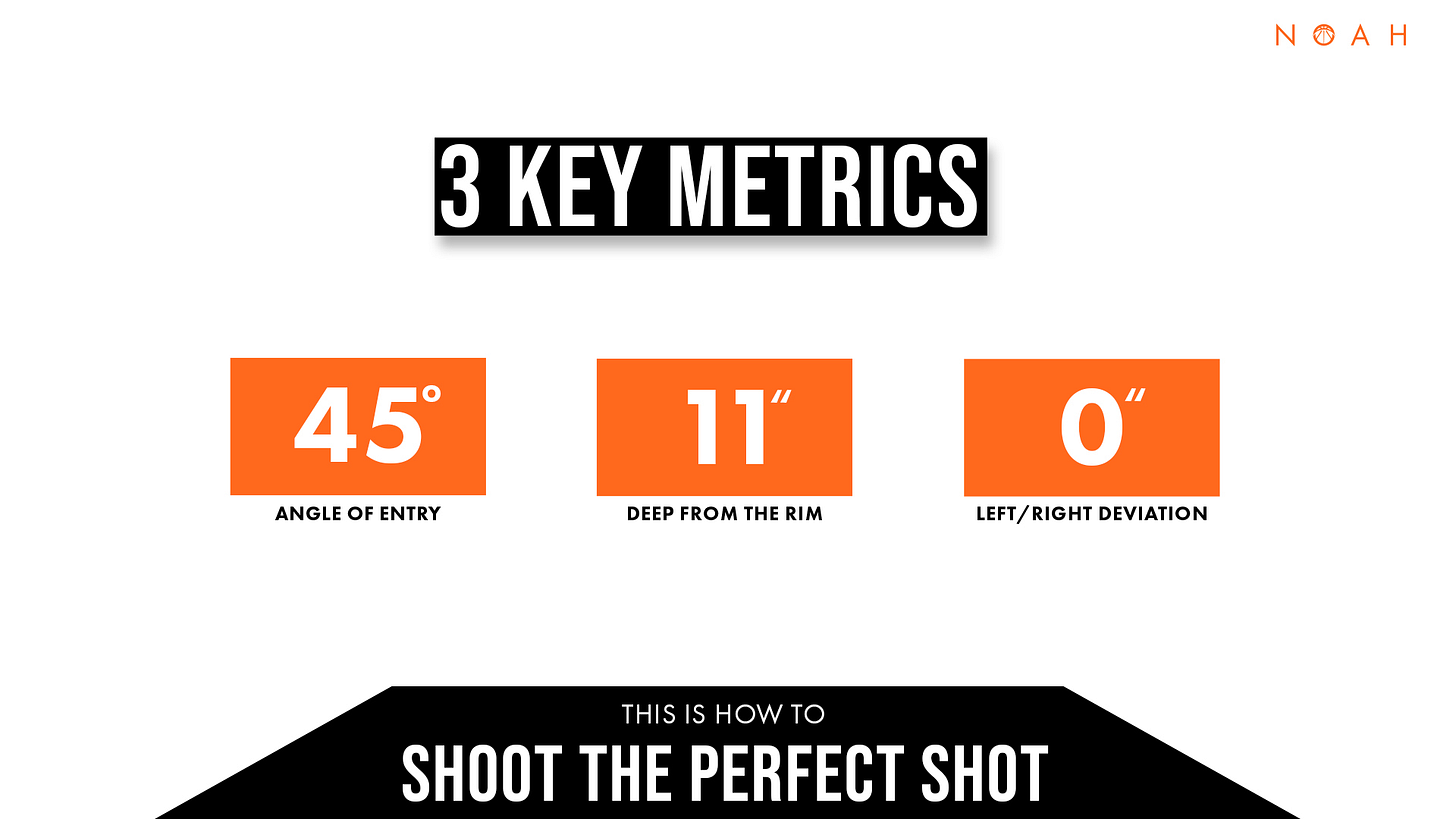

NOAH says that, after witnessing millions of shots, too, it has “cracked the equation” for perfect shooting metrics. Its philosophy is that the ball should enter the rim at a 45-degree angle, which represents the precise amount of arc while reducing the largest amount of variance in depth. As for the depth, the center of the ball should be 11 inches past the front of the rim. (A rim is 18 inches in diameter, so toward the back half — confirming the NC State findings).

45/11. That’s become the NOAH slogan.

Repetition without repetition

What NOAH and the NC State professors are giving you is a lot of numbers and calculations, and I’m not a numbers guy.

Which is why I want to think about what both the NC State professors and NOAH Basketball are suggesting not as analytics but as constraints.

A constraint is… like an obstacle. Your goal is to get from A—>B. You have to do so by factoring in a series of obstacles, C, D, and E.

Let’s say you’re a blacksmith. Dated reference, I know, but bear with me. You’re a blacksmith and you’re hammering. Your goal is to strike an object squarely each time with a hammer. That’s A—>B. Your constraints are that the hammer is heavy, you’re growing more tired with each stroke, maybe the conditions in your workshop are breezy (I don’t know!), or there’s a fly buzzing around your head, or you just had elbow surgery. These are constraints. You have to consistently reach your goal working within these constraints.

Nikolai Bernstein, a Soviet neurophysiologist in the early 20th century, one day was watching a blacksmith do just this. And he noticed something quite interesting. The path of the blacksmith’s hammer was rarely consistent, and yet it always seemed to land squarely on the object each time.

Recordings of hammering movements (Bernstein, 1967); the arm and hammer movements are added for illustration (Sternad, 2006)

Bernstein illustrated that for any goal-directed movement, our central nervous system (CNS) is confronted with an abundance of motor options to achieve it, if you consider things like joint degrees of freedom and muscle activations. This produces, he said, “repetition without repetition,” or a lot of variance in the production of a repetitive solution to a task. We can get to B a lot of different ways starting at A. In fact, the motor system isn’t really designed to function exactly the same way over and over again. There’s stuff like motor noise, feedback, and muscular fatigue that conflicts with our ability to precisely repeat motions. Try signing your name over and over again and see how variable the signature will look. We’re not robots.

This idea has spawned a lot of other ideas about motor control. But where some (but not all) in the sports-science community have landed gets us back to constraints.

Given that two movements aren’t exactly alike, that variance is inescapable partly because of the abundance problem for the CNS, then how we achieve a movement, frankly, well, doesn’t matter.

What matters about the movement is whether it achieves its goal within the constraints of the task.

Sorry for the jargon! Let’s get back to jump shooting for a moment. And I’m not referring to free-throw shooting here. Shooting within the context of a basketball game. The constraints are the physics of basketball, i.e. that the ball should be launched at a certain angle (52 degrees), and enter the rim at a certain angle (45 degrees), and that it shouldn’t be too far left or right, etc. But there are also constraints like fatigue, sweat on the fingertips, whether a defender’s arm is blocking the path of the ball, and how the CNS executes its motor control.

Clark’s “perfect” shot certainly seems to conform to the physics of basketball, but other constraints are more subjective. If your perfect shooting form doesn’t consistently get over the outstretched hand of a defender, then it doesn’t matter how good it looks. You’re going to need to change it.

Haliburton’s “ugly” shot seems to both conform to the physics of basketball and the subjective constraints that fit his CNS and other physical properties. I can’t imagine how many “shooting gurus” over the years told him to fix his mechanics to create a shot that’s more aesthetically pleasing. I’m glad he didn’t listen. Repetition without repetition.

Fundamentals vs. Constraints

We’ve talked before about the building blocks of skill learning, but I often wonder about the “fundamentals” of any skilled task — how have they been derived? Is it with consideration for the constraints of the task? Or is it to fit some aesthetic ideal of how it should look?

Mechanics are important, yes, but they become superfluous the further they get from the task’s constraints. That is both the physics of how the objective can be optimally achieved and the subjective constraints of the performer.

Coaches generally teach how they’ve been taught, so if they’ve been taught to shoot a basketball with a certain form, that’s probably the form they’re going to teach. Maybe that involves the right hand cradling the ball with the elbow precisely parallel to the ground. Maybe that grants most shooters the best stability to reach the preferred launch angle while initiating the most backspin on the ball.

All good! Then a Tyrese Haliburton comes along, and, well, his body is just different. He’s lankier and twitchier and whatever-ier, and so his route to achieving proper backspin and launch angle is a little different, a little quirky. If he tried to conform to the Caitlin Clark-ideal of a jump shot, he’s then adding constraints to his technique because it’s unnatural, it’s inauthentic. Not what you want. Better to give his CNS the freedom to get him from A—>B.

Apply this thinking in other activities. A golf swing is perhaps the most mechanized action we experience in recreation. Think about all the mechanics you’re told to think about to consistently hit the ball. Some of them are dictated by constraints such as physics or fatigue, but are all of them?

Would some golfers be better off if they were trained simply to think: What’s the goal? What are the obstacles? And how can your movement consistently achieve that goal given those parameters?

Ultimately, that’s what you want. Right?

People often ask, why doesn’t anybody shoot like Larry Bird? Why aren’t there any batting stances like Gary Sheffield or Rod Carew? Why doesn’t anyone throw like Randy Johnson or swing like Jim Furyk? It seemed to work for them! I suspect the answer is that we’ve been coached away from quirkiness, in pursuit of a one-size-fits-all ideal of what the mechanics should look like.

That may appeal to the constraints of physics, but it might fail to account for the theory of “repetition without repetition,” that no two bodies are alike and no two movements can be the same. I suspect it has cost sports a lot of colorful and memorable characters. That’s a shame.

What’s the downside to being perfect? It’s sorta, kinda dull.

Links

Do baseball scouts have a future? … First ECG study of WNBA players finds lower rates of abnormalities than men … “Boxer is Using Science to Track Her Brain Health” … How Do Olympic Athletes Sleep? Not well … Popular Supplement Nitrate Only Boosts Men's Athletic Performance … Smart rings’ ultra-precise movement tracking takes wearable technology to the next level … Quantifying Change of Direction Movement Demands in Professional Tennis Matchplay … Is massage therapy for runners worth the hype? … Inside the mind of Roger Federer

References

Tran, Chau M., and Larry M. Silverberg. "Optimal release conditions for the free throw in men's basketball." Journal of sports sciences 26.11 (2008): 1147-1155.

Sternad, Dagmar. "Stability and variability in skilled rhythmic action—A dynamical analysis of rhythmic ball bouncing." Motor control and learning. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2006. 55-62.

Interesting piece, Zach!

I’ve taught shooting to NBA players for the past six seasons. I blend a little of how I was taught to shoot, my approach from film study, and feedback from being on the court working with players.

My clients have averaged about a 6-point jump on their three-point percentage on multiple times their volume from the previous season.

The numbers/data that NOAH and the NC State project refer to are “symptoms” of the shot. Like a runny nose is a symptom of the flu.

If you focus on solving the symptoms (launch angle, drop angle, etc.), you will have a more challenging time improving your shooting.

You must start at the root of the bad habits that create the symptoms.

Really interesting Zach - made me think of this article from years ago about batting in cricket:

https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/ed-smith-why-the-perfect-technique-is-the-one-that-disappears-792155#