The “no practice” way

Cam Smith is a 30-year-old Australian currently playing on the LIV golf tour who is widely recognized as one of the game’s great putters.

He led the PGA Tour in fewest average putts per green in regulation two years in a row. En route to winning the Open championship in 2022, Smith rolled in 255 feet of putts in the second round alone. Do the math. That’s more than 14 feet per putt. It’s a figure that’s never been reached, anywhere, anytime, on the PGA Tour since it started keeping such stats in 2004.

Yeah, so Smith’s a remarkably good putter, which has naturally prompted a lot of inquiry into what makes him so good. There have been several articles and videos about his mechanics and his practice routines and his mental imagery. And there’s something else:

I’ll admit I am intrigued by this. I play golf, and as long as I can remember, I’d been taught that it was good, after lining up a putt, to simulate a few strokes before stepping up to the ball. It’s like taking a few cuts in the on-deck circle. Given that golf doesn’t have a clock, it never occurred to me that there may be a downside. But Smith apparently thinks there is.

“Rather than feeling through body motion, I like to just visualize it,” Smith said. “I like to take a really long look at the hole before I putt and see that ball dripping over the edge and then just hit it.” Golf.com

A TikTok video about Smith’s “secret to putting” probes a little deeper. It says that “neuroscience might explain why” Smith doesn’t take a practice stroke. Hmm.

The video references a scientist named Izzy Justice who has supposedly “scanned 6,000 brains while putting” for a recent study. That’s, well, A LOT of brains. It’s hard to fathom that he somehow got enough volunteers to fill a minor-league baseball stadium and don EEG caps while putting. Were they human brains? It’s unclear. I couldn’t find any such study, or any previously published studies by Justice on Google Scholar or PubMed.

I reached out to Justice for more details on his findings, his methodology, and where any of his research can be found. Haven’t heard back.

So for now, let’s just say I’m dubious of the reporting that “the results found that doing a practice stroke had a negative impact on the brain 95 percent of the time” and leave it at that.

Worse, the video goes on to explain that “putting is difficult” because “we don’t keep our eyes on the target” (?), which “means our brains have to remember where the target is.” Practice strokes “distract our brains from the target,” and then “communication from brain to muscles is scrambled, leading to missed putts.”

Sigh.

That sound you hear is me banging my head against the desk.

Listen. I know dissection of a TikTok video is uncouth and not worth the time, but if the video is suggesting that practice strokes will give you an actual stroke then something must be said. Must be said.

I don’t even know where to begin on the whole “eyes on the target” theory in there either. No, golfers do not keep their eyes trained on the hole as they putt — and this is not some unique golf phenomenon! A whole established line of scientific theory, known as the Quiet Eye as coined by Joan Vickers, is backed by study after study on high-level athletes in sports from hockey to basketball to, yes, golf — and the consistent theme throughout is that action moves too quickly for the eyes to follow, so performers focus intently on some fixed part of the ball or body in order to predict what’s going to happen. There are schools of “Quiet Eye Training” for golf that tell you to fixate on the back of the ball while putting. The brain does just find remembering where the target is. (Perhaps this is a post for another day…)

But, again, Cam Smith and others like Patrick Cantlay and Rory McIlroy have had success abandoning the practice stroke. So is a warmup swing overrated? Or, worse, detrimental?

An actual study on practice strokes

There is, in fact, an excellent study on whether practice strokes are helpful or harmful for putting that did not require the scanning of 6,000 brains.

Yumiko Hasegawa, a sports psychologist at Iwate University in Japan, and two others (Akito Mirua, and Keisuke Fujii) published a study in 2020 with the affirmative title that “practice motions” do “drive the actual motion of golf putting.” Among their findings: players are more accurate when they take a practice stroke that’s designed to mimic the stroke they’re intending to make.

While this sounds totally obvious, the researchers’ study design to reach that conclusion was actually quite elegant and fascinating. Their study included 10 professional golfers and 11 amateurs (really intermediate golfers with a median handicap of 14.5 — my kind of player). Each player took 48 putts toward a target, which was a golf-hole sized light beam projected on the ground. Before putting, they were allowed to make practice strokes toward the target they saw projected. But when they stepped up to the ball, the target disappeared. At random, it might reappear in the same spot it was before; other times, it was moved closer or farther away.

The players were given just one instruction: “Make practice strokes with the intention of hitting the presented target.” They never lost sight of the target, and there was no time limit with which they needed to hit the ball. They could also take as many practice strokes as they prefer (players averaged 2.68 practice swings per attempt). On a few trials, the players were also asked to hit without any practice strokes at all.

If these practice strokes mattered, the researchers surmised, they should improve the accuracy of the putts toward the unchanged target, since that’s the target that they were practicing to reach.

What happened?

When the target changed, accuracy dropped.

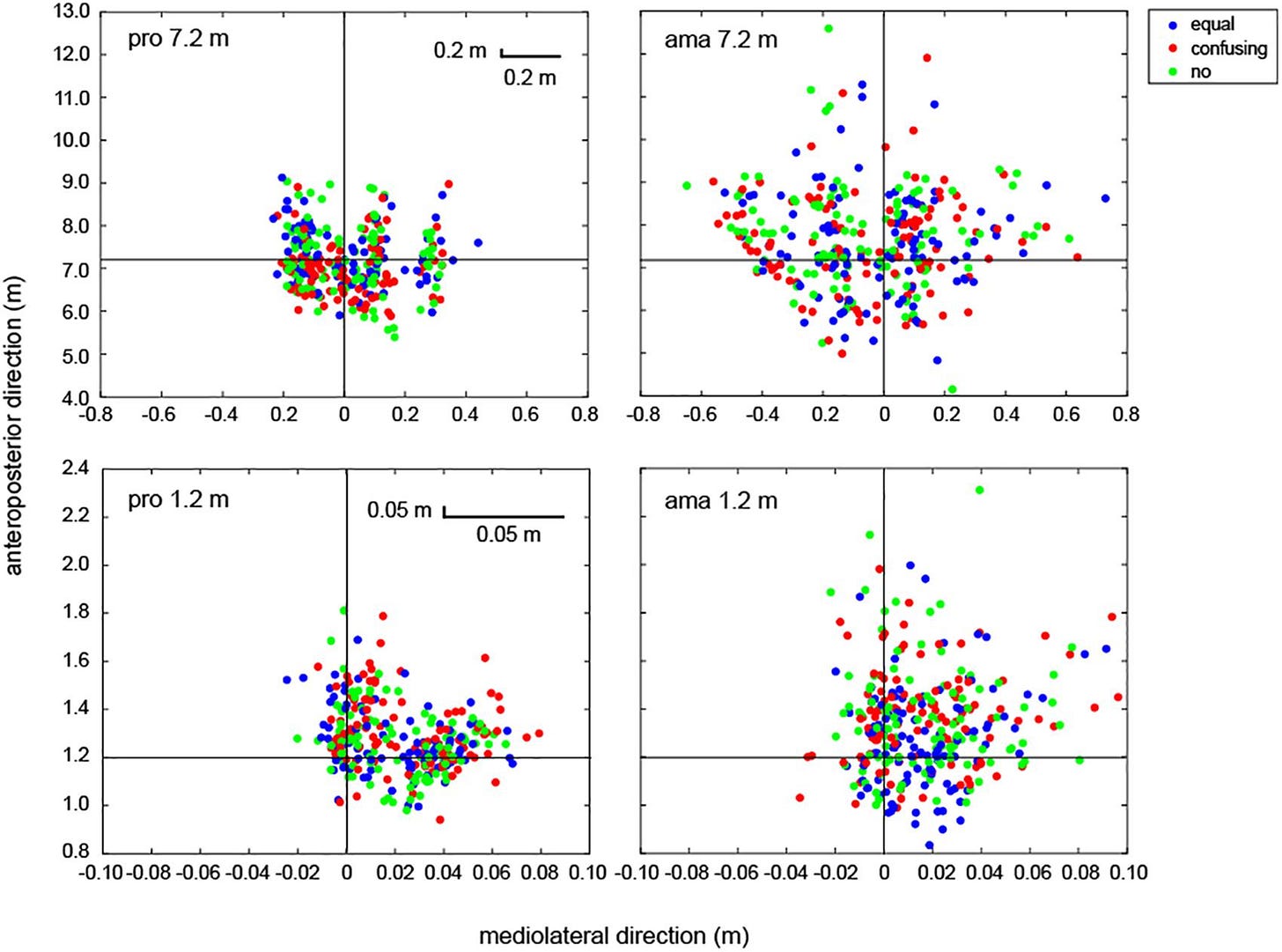

Here’s a dot plot of the putting results gathered by the researchers:

Left side are the professionals and right are the amateurs (in case you couldn’t tell from the scattering). Blue dots represent the putts when the target was consistent with the practice strokes (equal); red are when they target distance changed (confusing). Green is when practice strokes weren’t allowed (no). And the point at which the black horizontal and vertical lines cross indicates the center of the target.

Clearly, the pros are more accurate than the amateurs in any condition, but everyone was consistently more accurate when they were given a target that matched what they had seen while taking practice strokes. Even the pros had some struggles when the target was “confusing,” particularly if the distance was shorter.

But why were the amateurs so much worse? The researchers used motion-capture cameras to record the kinematics of the club heads. They found that the impact velocities of amateurs were way higher than professionals when they couldn’t rely on their practice strokes. This caused them to hit the ball harder than they should. It’s a function of motor control: professionals with a lot of practice are more adept at controlling precision forces. For amateurs, “practice strokes may function as a warm-up,” the researchers said, “that prevents excessively hard hits during actual strokes.”

So there is a function to a practice putt if you’re an amateur: It’s to prepare your motor system for the impact velocity necessary to control the distance on the putt.

This requires taking a practice stroke that accurately represents what you want the real stroke to be, and velocity here seems to be the key. If you’re lining up a 4-foot putt, try to make sure your practice swing reflects that distance. Gauging that tempo requires practice and experience. But it seems that an amateur player who doesn’t take a practice stroke will have a harder time preparing the motor system for that appropriate impact velocity.

I’ve heard this from golf coaches who advocate against practice strokes: Your practice stroke is inherently different than your stroke when making contact with a ball. This is probably true, but then why practice anything? Anything that’s simulated is inherently going to be different from the task in the field; what two shots are ever the same? Practice is about building a motor action, a “muscle memory,” that can be retrieved quickly and consistently while remaining flexible enough to handle uncertain scenarios.

But is there any benefit to practice strokes for a pro?

Well, something did strike the researchers as odd: When the target was positioned much farther away than it had been during their practice stroke, or they had no practice stroke at all, the professionals undershot the ball a lot more often, more so than even the amateurs. “It is possible an increased number of undershoots from only a few experts could have caused these results,” the researchers said, but analyzing individuals also revealed an exaggerated tendency to undershoot the target.

So, from this study, practice strokes for a professional seem to have the opposite benefit as they do for an amateur: Instead of assisting motor control, they seem to aid distance control.

The pros did exhibit a method of counteracting the “confusion” when shown a target they hadn’t just practiced for: They paused for significantly longer before taking a shot. That extra pause was because they “took longer to plan their motor execution,” the researchers speculated. They had to think harder through their shot.

Why do practice strokes matter?

I think it’s still important to unpack a little bit more about why a practice stroke might or might not be helpful.

Hasegawa et. al pretty nicely suggests there are motoric benefits to establishing the parameters of what you’re targeting — how hard or soft you want to hit it — with a practice stroke whether you’re an amateur or a pro (but especially if you’re an amateur).

Another thing to consider, though, when practicing or warming up for any skill is what am I actually practicing.

I like to say something that sounds fairly obvious: Your brain is not there to just play golf. No one was born to play golf. Your brain has a lot of other responsibilities, such as, you know, keeping you alive! Reminding you that you should eat a snack at the turn. Making sure you don’t get run over by a golf cart as you’re walking down the fairway. This sort of thing.

And so when it is time to execute a skillful task, like a putt in a professional tour event, it may require a certain recalibration to tune itself out of “watch out for that golf cart” mode and back into “now I need to putt” mode.

This is achieved through a psychological rejiggering — ie., focus. Sure.

I tend to think it may benefit from a motoric reminder as well. To stick with golf as the example, going from walking down the fairway and pacing around the green to standing static over a ball and delivering a delicate stroke toward a distant target is, well, a lot to ask of your motor system.

For pros, and amateurs, a practice stroke on the putting green might not just be for distance control or motor control. It’s a motor reminder.

Different strokes for different folks

I know there are going to be people emailing me or commenting with the counterargument: If it works for Cam, why fix it?

I recognize that many performers are creatures of habit (and superstition), and pre-shot routines and confidence make up a big part of enabling their “it” factor. Messing with that routine or habit, and thereby shaking that confidence, simply might not be worth it. So if it indeed works for Cam, there probably is no reason to fix it.

I’m simply providing a case, rooted in science, for why practice strokes on the green are beneficial for putting accuracy.

And please let me know next time you see a TikTok video saying “neuroscience explains why.”

Links

Elite athletes demonstrate higher perceptual cognitive abilities compared to non-athletes … “By mastering the art of body language, we can gain an edge, not only by enhancing our own performance but also by influencing the psychological state of those around us.” … Expert cyclists say stuffing a water bottle down their shirt gives them a critical aerodynamic edge. … Why Going on a ‘Sex Ban’ Probably Won’t Help Tiger Woods … The power of human touch: A friendly pat on the back improves basketball performance … How does weed affect a workout? … Does a more diverse team play better? … Does hand size matter in the NFL’s trenches?

References

Hasegawa, Yumiko, Akito Miura, and Keisuke Fujii. "Practice motions performed during preperformance preparation drive the actual motion of golf putting." Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2020): 518391.

Yumiko Hasegawa, Keisuke Fujii, Akito Miura, Keiko Yokoyama & Yuji Yamamoto (2019): Motor control of practice and actual strokes by professional and amateur golfers differ but feature a distance-dependent control strategy, European Journal of Sport Science, DOI: 10.1080/17461391.2019.1595159