Let’s say you’re Patrick Mahomes.

You’ve gotten to the Super Bowl again because you’re extraordinarily skilled. You’ve got a great arm, great vision, you eat great breakfasts, you listen to great podcasts, you are greatness personified. Your team (the Kansas City Chiefs) has beaten up on all the lowly competition all the way up the ladder to the Big Game, where you’re going to have a rematch against the San Francisco 49ers, a team you also faced in the Super Bowl a few years ago.

The 49ers have two weeks to prepare to face you, instead of one. And, really, you’re not much of a secret anymore. Everybody knows you’re pretty good. You’ve been in the league now for six years, and you’ve won almost every time you take the field, so there’s a lot of interest from competitors in knowing your tendencies and studying your habits.

Athletes are prediction machines. They spot patterns and cues in the heavily rehearsed movements of their opponents that help them predict what’s going to unfold. Batters hone in on the release of the ball out of a pitcher’s hand to predict the pitch type. Basketball players watch a shooter’s follow-through to set up for a rebound. NFL defenders track the quarterback’s eyes to get a jump on his intended receiver.

Athletes sort’ve do this intuitively, or they’re coached to do it, or they learn about it via trial and error. But another critical part of developing skill is not just recognizing the patterns that you need to form your predictions, but also recognizing the patterns that your opponent needs to form their predictions.

And so, you’re Patrick Mahomes. And you know that defenders are going to try to read your eyes on a downfield pass in order to predict the intended target. And so you do this:

That’s a no-look pass. From a quarterback in an NFL game. It’s not just a play that looks cool for highlight reels. Mahomes has introduced a means of deception that throws off a great defender’s ability to predict what’s going to come next. He recognized a perceptual cue used by his opponents and stripped it from them.

When you’re Patrick Mahomes, and you’re pretty much the most heavily scrutinized football player on the planet, your skill alone sometimes isn’t enough to give you an advantage. Because when you’ve reached the point of being a world-class athlete, everyone else in that class is also pretty good, and also the population of that class is pretty small. When you’re a good juniors tennis player, there are 5 million others like you. When you’re Novak Djokovic, there may only be 5 or 6 others at your general level. Invariably, you’re going to meet them time and time again in big matches.

The more you face somebody, the more confident you can be in your predictions about their intended actions. Deception is one way to break that cycle, and it’s not used enough.

The subtle art of disguise

The truly great ones, however, do apply deception to their skills with regularity. There was a fascinating study that published in 2022 in the International Journal of Sports & Coaching from researchers at Waseda University in Japan called “The importance of disguising groundstrokes in a match between two top tennis players (Federer and Djokovic).” They analyzed the second and third sets of the 2019 Wimbledon men’s final, a 5-set classic between Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer, two greats who were meeting each other for the 47th time as professionals. A frame-by-frame analysis of the official match video was used to judge whether each groundstroke had been disguised — or the cues for the ball’s direction before contact was different than the actual post-contact ball direction.

One reason why I liked this study is that one of its authors, Milos Dimic, is a certified professional tennis coach. This gave the group some important authority in making observational judgments about the 299 strokes they were analyzing. He could tell from watching the video whether the hitter was purposely disguising his stroke. And, it turned out, they subtly disguised their intended hits many, many times.

You may wonder how researchers can claim to know intention by watching a video tape. This is where it’s also important that the author is a skilled tennis player and coach. He could recognize how a shot should behave based on the mechanics of the setup and the swing. When the mechanics didn’t align with what the researchers termed a “kinetic chain concept for optimized movement,” it was presumed that the player was purposely changing his body and racket orientation with “the intention of disguising stroke direction,” the researchers wrote.

These are subtle disguises! The researchers didn’t only look at the hitter; they examined the receiver, too, to determine if he’d been fooled. Tennis experts typically utilize a so-called split step, or a tiny hop, in anticipation of an opponent’s stroke, which enables them to react quicker. They tend to initiate a response even before landing from that small hop. The researchers judged whether the receiver was deceived by the hitter based on his posture at landing.

Cues of deception

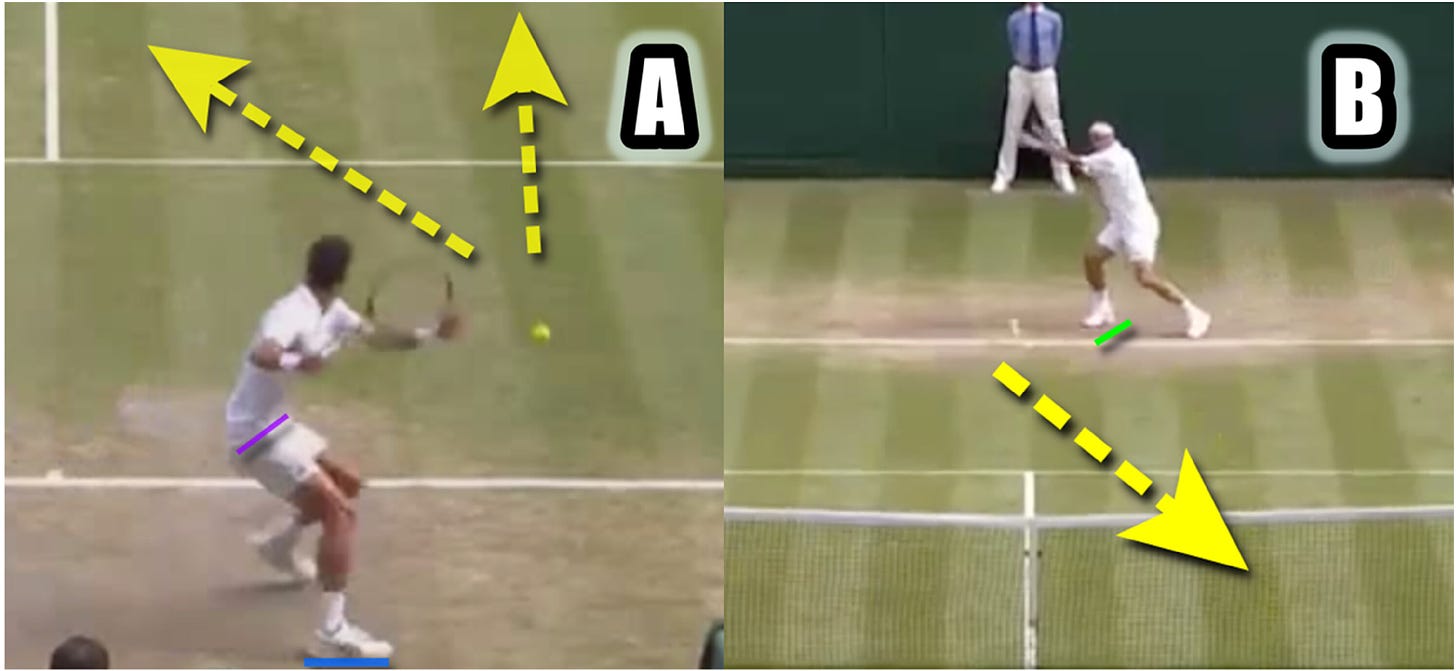

A few disguises may be noticeable to the naked eye, if you know where to look. When the loading foot on a groundstroke was placed parallel to the baseline, the shot intention becomes more difficult to judge because the foot’s placement enables more trunk rotation. A loading foot placed perpendicular to the baseline limits the trunk rotation — and thus limits the shot possibilities.

A) parallel loading foot = many shot possibilities

B) perpendicular loading foot = fewer shot possibilities

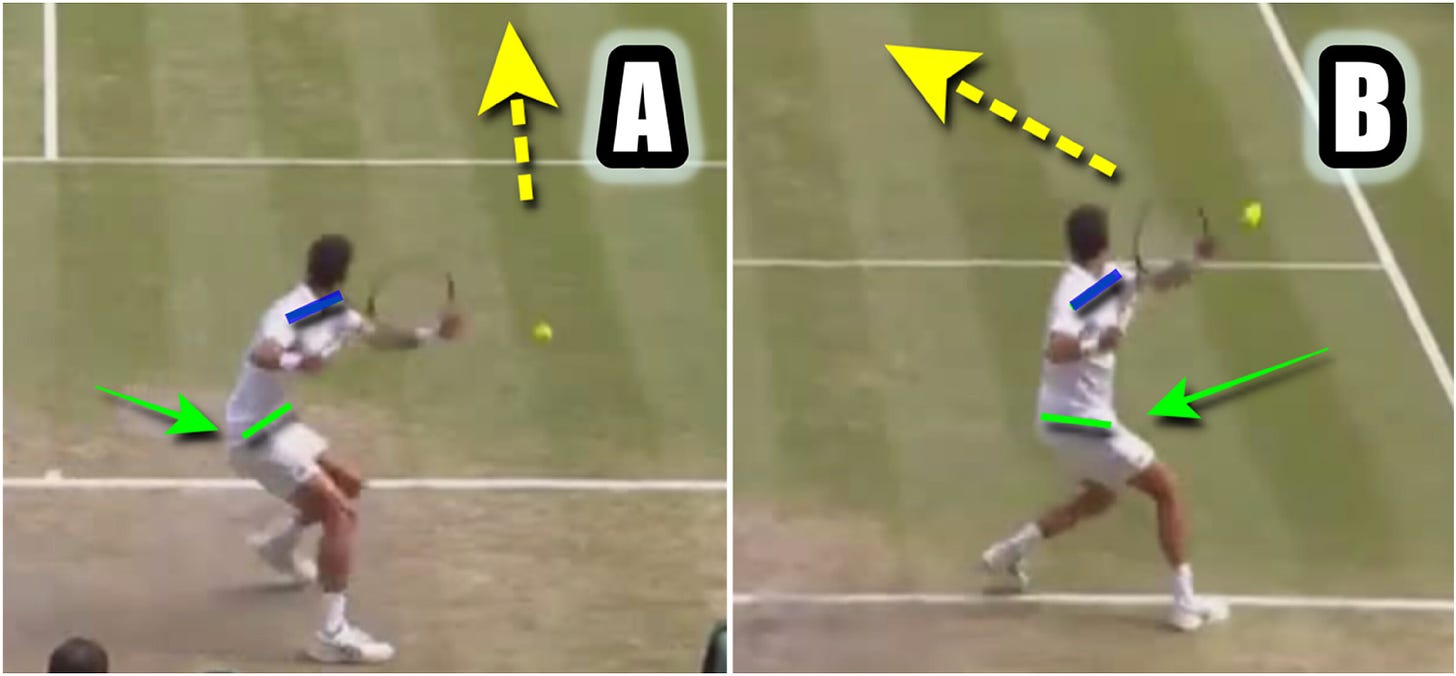

Another focal area for deception is the trunk, meaning the hip and shoulder. When players intend to hit a ball down the line, their hip rotation angle tends to be larger/pointier (for both forehand and backhand), and shoulder rotation angle tends to be smaller/flatter. On an intended cross-court shot, it’s the opposite. See the image below.

Blue line: Flatter shoulder rotation angle, large hip rotation angle = down the line

Green line: Larger shoulder rotation angle, flatter hip rotation angle = cross the court

Knowing this, skilled players can mess around with the angles that keep their opponents guessing. I can dive deep into the neuroscience of motor action and how our brain is constantly building models of action based on predictions of the movements before we actually engage them. But this being a newsletter, I’ll keep it light.

The bottom line is that experience with a task (like tennis) fortifies those models until the prediction becomes somewhat automatic. Clever deception forces opponents to have to make fresh predictions all over again.

So, who was better at deceiving whom?

Of the 299 strokes by both players in the two sets, the players disguised their shot a staggering 83 times, or 28 percent of the time they were hitting. Those disguised shots either won them a point or gave them an advantage toward winning a point 58 percent of the time.

Drilling down further, Federer came out roaring in the second set, which he dominated, 6-1. The researchers found that Fed was all over Djokovic’s undisguised shots, successfully anticipating on 17 of his 18 attempts. He had more difficulty, however, when Djokovic disguised his shots (4 of 9). It’s possible that Djokovic recognized this and adjusted, disguising more of his shots in the third set. Federer continued to struggle anticipating with Djokovic’s increased use of deception, incorrectly predicting 21 of the 23 points that Djokovic had disguised.

Noteworthy, too, is that Federer’s success anticipating Djokovic’s undisguised shots also collapsed, probably because he was made hesitant by all of Djokovic’s trickery. His prediction mechanism had been thrown off. Even the great ones can’t always rely on skill alone. Deception can be a great equalizer, and it can also be a crucial advantage — especially against an opponent that thinks he knows you well. Djokovic won the set, 7-6.

As mentioned, the researchers only analyzed those two sets.

But, spoiler alert: Djokovic won the match.

Helmet orientation

Btw, I mentioned earlier that Mahomes uses a no-look pass to keep defenders guessing about his intended targets. Well, sometimes the uniform can do that work for him.

In 2015, researchers at a thinktank in Washington, D.C., actually examined whether the helmet colors and logos of college football teams might hurt or hinder the quarterback, the theory being that certain stripes and logos on the helmet could stand out more and therefore make the quarterback’s head orientation (and gaze) more predictable for the opponent. This study was awarded $17 gazillion dollars by the presidents of the SEC schools (I’m kidding - but seriously).

In fact, they found that having a stripe on the helmet did correspond with a higher percentage of interceptions per pass attempt. Why? The researchers wouldn’t speculate, other than to suggest it may offer a clearer giveaway of the quarterback’s head orientation. Nobody entertained the idea that better players might play for teams with more modernized, stripe-less helmets, but hey, who am I to judge?

Links

Why are there so few multi-sport athletes nowadays? … Brain training a new frontier for football. … Study: Static stretching could build as much muscle as lifting weights. … Five out of seven women in the study who had children during their careers managed to return to the same competitive level as before pregnancy, or became even better. … We must tackle female ageism in sport. … Muscle contraction time after caffeine intake is faster after 30 minutes than after 60 minutes. … Termed "target panic" by Olympic and World Champion archers, this struggle presents as a hesitation in releasing an arrow. … Researchers are one step closer to diagnosing CTE during life, rather than after death. … Playing a musical instrument or joining a choir is linked to better memory and thinking skills in older age. … This is Palm Springs Surf Club, a new state-of-the-art wave pool that’s bringing surfers to where they never thought to hang ten before: the middle of the desert. … Tech Libertarians Fund Drug-Fueled ‘Olympics’ Where ‘Doping’ Is a Slur

References

Sawyer, Michael W., Christian Buchmann, and Corey A. Kalbaugh. "Examining the impact of helmet orientation visual cues on the passing effectiveness of quarterbacks in American football." Procedia Manufacturing 3 (2015): 1181-1186.

Dimic, M., Furuya, R., & Kanosue, K. (2023). Importance of disguising groundstrokes in a match between two top tennis players (Federer and Djokovic). International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 18(1), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541221075728